Vacant houses. We have a lot of them in Cleveland. About 12,000 at the last count, out of 158,000 parcels overall. Not a surprising outcome for a city that - although it’s making a lot of great strides in creating new jobs and drawing new residents to some neighborhoods - has been losing population for a long time. To the suburbs, to sunnier regions with more jobs, to the 2008 foreclosure crisis.

It’s easy to look at a vacant house, especially if it’s fallen into disrepair, and think - well, obviously nobody would want that. Probably we’d be better off if it were just torn down.

But what I’ve heard from spending time in the neighborhoods of Buckeye, Woodland Hills, and Mount Pleasant — which together have about 3,500 vacant houses — is that that’s not true. There are responsible people who want vacant houses. Who want them a lot. And for really good reasons.

This episode is all about one of those people. A woman named Kim Fields, who’s been on a 5-year-long quest to buy and renovate two empty houses - and not just any two, but the two on either side of her.

For Kim, the goal isn't monetary gain, though she’s confident she could at least break even by renting the houses out. It’s about saving her neighborhood: The place where she’s lived practically her whole life, a place that she sees as still strong, still valuable, and not just for memories of the past but for what it offers now.

Luke Easter Park. Easy access to the museums and hospitals of University Circle. And most of all, people. People like Donald Wilson from Season 1, who builds the Red Tire Project. Proud older African-American couples who were able to buy their first houses here decades ago, and never left.

At the time I heard about Kim’s story, despite all her efforts, she kept hitting dead ends. No one seemed to be able to tell her what she really wanted to know: How she could buy the houses and fix them up.

"I was sending emails, I was sending letters," she says. "I was calling the councilman so much that he would be like, 'Yes, Ms. Fields.'"

On this episode of Sidewalk, Why is it so hard to buy that vacant house next door to me? So I can fix it up and help save my neighborhood?

A plan to fix up houses

Kim Fields is in her 40s, with an easy smile, usually soft-spoken, but firm when she needs to be.

When I meet with her at her two-family house in the Woodland Hills neighborhood, she's wearing a brightly colored shirt and black slacks, with simple earrings and jewelry. She’s been a resident here her whole life, and a homeowner for 15 years. She lives in the downstairs unit of her house with her dog Sadie and some really great old furniture: a 1950s radio, fancy upholstered chairs.

When Kim moved into this neighborhood, it was full of people. These days, though, she feels a bit like she’s living on an island. There are empty lots across the street, and an abandoned house on either side of her, though one is occupied by illegal squatters. She knows from checking property records that both houses are tax delinquent, that the owners have pretty much walked away.

She doesn’t want to just throw in the towel and move away, like some of her neighbors have done. Her solution? Buy the two empty houses, fix them up, rent them out to responsible tenants. She has a whole plan to get older tenants for the downstairs units, younger tenants for the upstairs.

"They could help each other out," she says. "Maybe the senior wasn’t driving, the young person could take them to the store, the senior could help with day care."

The maze

Kim works for the Saint Luke’s Foundation, which funds this podcast and lots of other projects on the city’s southeast side -- everything from dental work for low-income kids to mural projects to healthy cooking classes. In other words, she knows people. And they know her. But even with her connections, she’s been lost in a maze of bureaucracy — for five years. She keeps a file folder of all of it, and it’s now about two inches thick.

None of it makes much sense to her. People are being responsive when she reaches out, she says. But nothing ever seems to happen. The houses just keep sitting there.

She’s given up on one of the houses - the one with the squatters. It’s just too far gone. But the other one, the one that’s vacant, she still wants to buy. And she’s worried, because even though she’s put up “No Trespassing” signs on the outside, and tries to help keep the yard maintained to make it look like somebody’s living there, she’s pretty sure lately she’s heard people breaking in at night, probably looting for appliances and copper plumbing.

That could mean that the house is on a path to being unsaveable, and will get demolished, like so many before it. That frustrates Kim, because once a house is torn down in a place like Woodland Hills, where housing demand is low - It’s unlikely that a new home will be built in its place. Every house that’s demolished is one less potential neighbor watching out for the street. One more vacant lot saying, ‘This neighborhood is in decline.’

"I think [demolition] is a strategy that has gone out of control," she says. "I think it’s like 'Oh, it’s vacant, let’s demo it.' We need somebody going into these houses with a good eye and saying, 'OK, the exterior doesn’t look good but the interior is OK and it has a solid foundation. And I think sometimes it’s easier just to say let’s just tear it down."

Kim says she knows the city’s population is going down, that people want to live in the suburbs or move away to cities with warmer climates. But to her, demolition can become a self-fulfilling prophecy. The more houses get torn down, the more people get the message that if they’re already living in Woodland Hills, they should get out. And if they’re considering living there, well - they shouldn’t.

If she could her hands on the house next door, fix it up, rent it out, that would obviously send a much more positive message.

"I’d just like to know either way if it’s rehabbable or not," she says. "And right now I don’t know."

I tell her I'm amazed she hasn't been able to get that answered.

"I know," she says. "Me too. I guess I don’t have any power."

Looking for answers

She says if she feels powerless, then she can only imagine how a lot of her neighbors must feel. People who aren’t plugged into the networks she is.

Because Kim - she’s not an isolated case. She’s talked to longtime neighbors who want to buy and renovate vacant houses just like she does, including Liz Bartee.

So Kim and I decide to set up a meeting someone who is in power. Or at least, knows a lot more about all this stuff than we do.

Lilah Zautner works for the Cuyahoga County Land Bank, which is officially called the Cuyahoga County Land Reutilization Program. We meet her in a conference room at her office downtown, big, color-coded maps of the city all over the walls showing properties that are risk of foreclosure or vacant.

In theory, at least, the Land Bank could be the place to help people like Kim. It acquires vacant buildings and either tears them down, or - if they’re still in good enough shape - renovates them. Right now, the Land Bank tears down about 60 percent of the houses it takes on, and oversees renovation of about 40 percent.

"One of the main reasons we were created was to stop the bleeding that happens within the housing markets, and to take the worst of the worst off the market," Lilah says.

The Land Bank got started in 2009, at the height of the foreclosure crisis. Its job is to keep track of empty houses in the city and make sure they don’t fall into the hands of out-of-state speculators who don’t really care about the neighborhoods. That was happening a lot a few years ago.

"As those properties are going through tax foreclosure, we file a paper that says send it to us don’t send it to sheriffs sale, because these properties are bad: They’re condemned or condemnable," Lilah says.

Tax foreclosure happens when an owner stops paying their property taxes, either because they can’t afford to or because they’ve just walked away from a house that’s lost most of its value.

Kim raises an eyebrow. One of the houses next door to her, the one she still wants to renovate? It’s way behind on its property taxes. Has been for years. And it’s still just sitting there.

"So is there anything from your end you can do to push that process along when a property is $30,000 tax delinquent when a community member is showing a strong interest?" she asks.

"Yes. Yes, definitely," Lilah says. "And that is where we say, call us."

The problem is that tax foreclosure, which is how the Land Bank gets control of most properties? It takes a really long time. First, the property has to be delinquent for a while -- usually at least a year, and with so much back debt that the owner probably can’t pay it off. Then, the county has to prove that the house is vacant, that no one is living there, even if they’re illegal squatters.

"You wanna say why did it take so long but on the flip side, they want to give every opportunity to avoid homelessness," Lilah says.

Then, once the property is proven vacant, it can go to county’s board of revisions which takes another 8 to 14 months to actually foreclose and send it to the Land Bank.

In other words, that house that’s been vacant next to Kim for five years? It’s not that atypical.

Kim takes this all in. She’s staying calm and polite, but I can see the frustration under the surface.

"I would think that as a community member like myself," Kim says, "if I’ve been complaining about a property, like the one next door to me, at some point if a councilperson or someone would say let me see how i can help you get access to this property."

Lilah says she agrees, that she wishes she could pull up the property record right now to look for answers.

Kim and I ask if we can just do that.

Lilah says yes, leaves to get her laptop. She comes back, types on her keyboard.

She logs onto this public website called MyPlace, which gives basic property information for every parcel in the city.

Lilah looks up the house Kim wants to buy. The information pops up, and Lilah kind of stares at the screen for a second.

"So we own it?"

Kim thinks Lilah’s asking who owns it, and Kim gives a name.

"No, we own it," Lilah says.

"Oh, you guys own it? Since when?"

"Oh boy."

Turns out the Land Bank already owns it. It transferred to them just two weeks ago. Kim never heard.

In this case, part of the reason the house took so long to come into the Land Bank’s system is that there were occupants, even after it became tax delinquent. Also, the owner may have filed for bankruptcy. In bankruptcy cases, the Land Bank has to wait for some of the legal paperwork to wrap up before they can step in.

Kim and I sit there, trying to process all this. What happens from here? Is this a good thing or a bad thing? Lilah keeps typing.

She says the Land Bank assessed the property a couple days ago, and determined it was a demo.

A demo. As in, a demolition.

"Just because we say it’s a demo doesn’t mean it has to be," Lilah says. "If somebody wanted to renovate it they could make the case."

Kim asks how they determine the house needs to be demolished.

Suddenly, we’re looking at a whole bank of photos of the inside and outside of the house. Taken just a few days before, probably while Kim was at work.

They're pretty grim. All the kitchen appliances are gone. The furnace is gone, and the hot water tank too.

The rooms are empty except for some piles of old clothes in the corners. The walls are ripped open, probably by a looter looking for copper plumbing.

I ask Kim how she’s feeling, seeing all these terrible pictures of the house she wanted to save, finding out it’s going to be demolished.

"I have mixed feelings," she says. "I’m happy and sad at the same time. I wish we could have done something with this property before it’s in the condition that it’s in now."

Lilah says if Kim wanted to renovate, and could prove she had the resources, the Land Bank could probably sell her the house for about a thousand dollars. The problem is, the average sales price of a house in Buckeye and Woodland Hills right now - is only $14,700.

I’m not great at math, but even I can handle this one. Someone buying this house would have, on average, about $13,000 to invest in renovations before they were under water.

Lilah says that wouldn't do it.

"I mean I’m not a construction expert but my guess is you’d need at least $30,000," she says.

By comparison, it only costs about $10,000 to demolish a house. Which is why houses that are being renovated in this neighborhood are usually done with sweat equity and elbow grease.

I ask Kim if she’s up for taking that on.

"Without giving it a whole lot of thought, I would say no," she says. "However, I could change my mind as I look at the property, think about some of the memories. But at this point I would say no."

On a bigger level, she says thinking about all this -- the low property values, the number of vacant houses -- it makes her think about her own continued presence in the neighborhood, which she’s grappled with for years.

"It’s like do you stay do you go, it’s that constant struggle of staying and going," she says. "And when you hear about the median housing values it’s like ‘Oh it’s time to go.’ But I need to stay to make an impact, if i go too I’m doing the community a disservice."

Lilah says she empathizes. Hearing people struggle with those types of questions is the hardest part of her job.

"It’s just heartbreaking," she says. "Because I just think every one of these houses was somebody’s equity and value."

And it’s not lost on her that of the houses likely to require demolition over the next few years? Almost all of them — 89% — are on the East Side, which is also where the city’s African American population is concentrated.

On the one hand, you might say, well, that just happens to be where the market is weakest. But on the other, there wasn’t an even playing field to begin with. There’s a history in this country of banks not giving black people mortgage loans. Of realtors using racial panic to scare white people away from a neighborhood when black people move in. Tearing down houses in black neighborhoods now - even if it’s intended to bring about good - it echoes that history.

"Especially in a neighborhood like Buckeye, these were houses of black families," Lilah says. "And to think that a whole group of people were able to come and become homeowners and create community and then in one generation for it to just be sucked away...

"You know, I’m happy to provide information and be part of the solution," she says. "But it doesn’t make up for devastation and how this has affected people’s families."

Managing a flood, with resources for a trickle

Later, I call up a guy named Frank Ford. He’s been working on this problem of empty houses in Cleveland for decades, so I figure he’ll have some good perspective on all the issues.

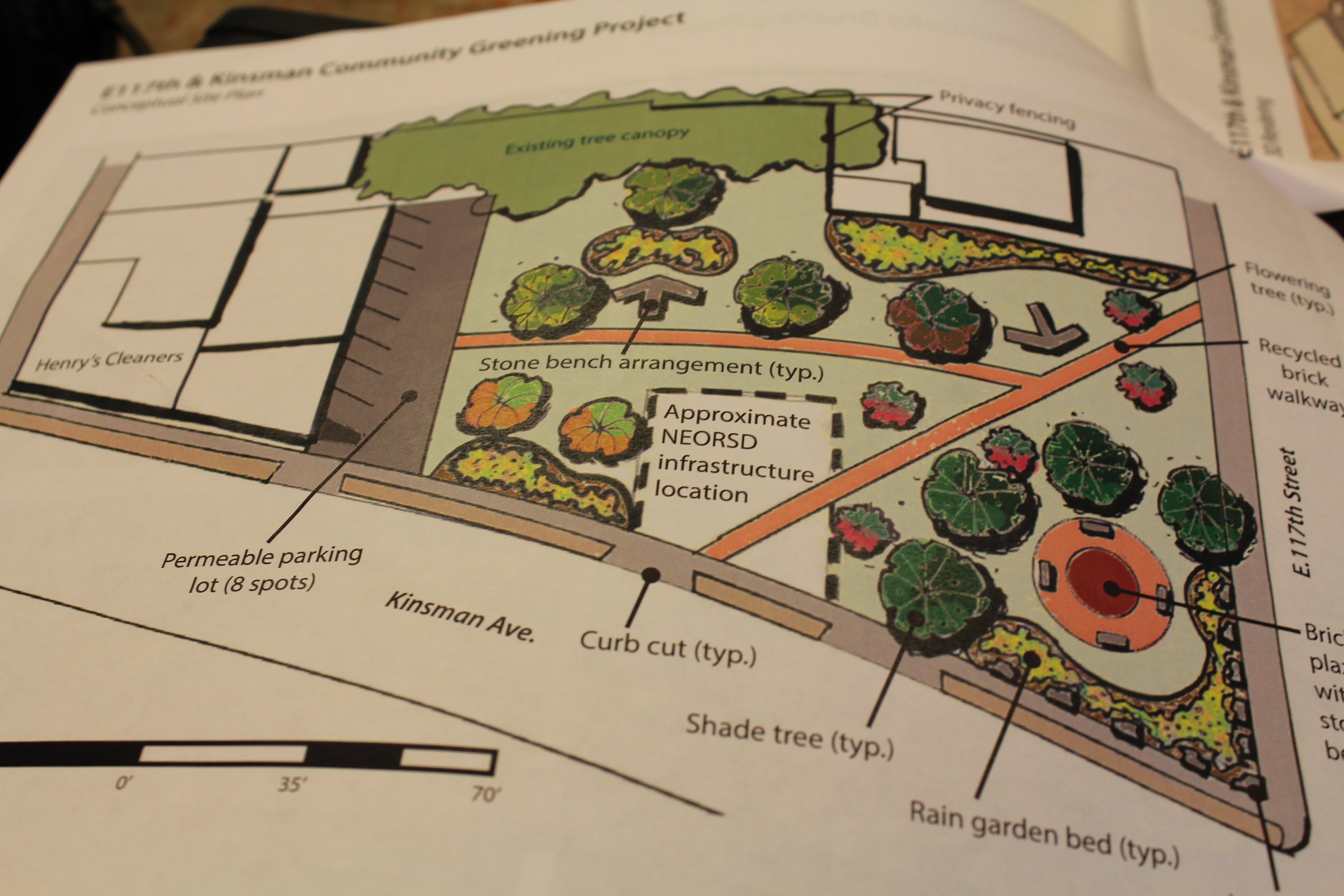

These days, he’s a senior policy advisor and researcher for the Western Reserve Land Conservancy, a nonprofit that tries to find new uses for Cleveland’s vacant land. Things like community gardens, parks, tree plantings.

"What you’re raising is a significant problem," he says. "You’ve got these vacant properties and once they go vacant there’s a period of time when they’re actually more salvageable."

The reason for that is lack of resources, he says.

Basically, the sheer number of houses going vacant, especially after the foreclosure crisis - it was a flood, and institutions in the city and county are set up to handle a trickle. Right now, there are about 12,000 vacant buildings in Cleveland, about 8 percent of the total number of parcels in the city.

Demolition maybe isn’t ideal, he says, but it’s a way to keep up. And it has a much more positive effect on property values than letting houses just sit and decay.

I ask Frank about a program I heard about in Massachusetts called the Abandoned Housing Initiative, where the state uses something called nuisance abatement to help neighborhood groups get control of houses from negligent owners.

He says that’s a useful tool, but usually as time-consuming as foreclosure. And Massachusetts isn’t handling vacancy at anywhere near the volume Cleveland has.

The good news is, 10 years after the peak of the foreclosure crisis, he says Cleveland and its inner ring suburbs are starting to catch up. Since the peak year of 2010, the number of vacant structures in the county has declined 35 percent, according to his research.

"There’s a point where you remove enough of the blight that you then create the market conditions and then we switch from the main strategy being demolition to a strategy being saving the properties by renovation," he says.

The Western Reserve Land Conservancy, where he works, has been sending surveyors out into the neighborhoods, looking at houses for signs that they’re vacant. The hope is that that data could help the Land Bank and other institutions intervene faster.

But even so, he says, surveys like that go out of date almost immediately. A longer-term and more effective solution may be a return to old-fashioned community organizing. Knocking on doors, talking to people, to see which houses are vacant, or at risk of becoming vacant.

I ask if instead of just looking for vacant houses, the Conservancy could also look for residents interested in doing renovations.

"That’s interesting," he says. "You know, traditional community organizing, where you’re going door to door -- it’s fallen by the wayside. But you’re mining for gold. Because you’re not only out there looking for issues but you’re looking for potential leaders. You’re surfacing people like a Kim Fields."

Still torn

A couple weeks later, after all this has had a chance to settle, I check back in with Kim at her office.

I ask if she’s still leaning toward letting the house get demolished.

"I’m really still torn," she says. "I have been pondering and praying and in deep thought, like do I renovate this home or do I just purchase the side lot."

She’s talking about a program where, if a house gets torn down, the neighbor can buy the empty land as a side yard for $100.

Right now she's leaning toward buying the side lot because renovating the house may not be justifiable given nearby property values.

But she says this is not a choice she should’ve had to make in the first place.

"I try not to reflect on it too much because it makes me mad," she says. "This was a home I had been reporting for so many years and before it got so bad, we could have done something! We could’ve absolutely done something."

She says she understands that dealing with empty houses is a big problem, and she knows now that if another house on her block becomes vacant and she wants to buy it, she can call Lilah at the Land Bank for help. She’s planning to tell her block club about it, too.

But she says there’s a problem here much bigger than her or her block. When most of the houses that are slated for demolition over the next few years are in African-American neighborhoods, saving houses themselves - that becomes only a small part of a much bigger goal.

"It’s about saving communities," she says. "It’s about saving communities, and then it’s about saving houses."

She gets a bit tearful reflecting on that.

"It’s like, this is your childhood where you grew up," she says. "And it absolutely makes you emotional because when you think about leaving your property on to your children, it’s like that might not be an option for them if we keep having all these vacant properties, if we tearing down houses. That won’t be an option for my grandson and his children."

To her, the solution to all this remains really clear.

"First," she says, "let’s find out why you can’t pay your taxes. If that doesn’t work, put [the owner] on probation, go to the next step of who could take over this property instead of letting it get to a [bad] condition.

"I know the city is overwhelmed with so many properties, but at the same time they’re losing so much money! In back taxes and stuff. So we need someone that’s bold enough to step in and say 'Hey, you’re behind on taxes, let’s see what we could do.'"

I ask if she’d want to be that person. She said yes, absolutely, if that job could be created she’d want to be the one to do it. She could see herself going around knocking on doors like Frank Ford talked about, asking people what she could do to help. Working with the mayor to figure out new processes.

"We need to figure out something different for our neighborhoods, because our homes are getting torn down, criminal activity is happening, drug activity," she says.

"We need to work with [the city] to develop a plan so that before these houses get to a condition where they have to be demolished, we can prevent that."

Now that the worst part of the vacancy crisis is over, now that things are finally stabilizing after 10 years of chaos - maybe this is just the time to come up with that new plan.