Usually, the daily commute is pure routine - a slog, even. But during one evening rush hour last fall, at the Shaker Square Rapid Station, the innate poetry of movement and interaction was brought to the fore. Authors Kisha Nicole Foster and Daniel Gray-Kontar showed up on the platform for some impromptu readings of their favorite work. A collaborative project of Twelve Literary Arts, LAND Studio, Anisfield Wolf Book Awards, Greater Cleveland Regional Transit Authority, and The Cleveland Foundation. Season 1 finale.

15: Blockbusting Buckeye

This post is an expanded version of my second collaboration with ideastream, Cleveland’s public media company. First, the story itself, and then I’ll spend some time afterward exploring some of the side questions it raised for me.

Back in the 1950s and 60s, the saying was that Buckeye had the largest concentration of Hungarians in the world outside Budapest.

Ernest Mihaly was one of them. His parents emigrated to Buckeye in the 1910s, and when he was a kid the neighborhood was full of Hungarian stores.

“We had about 8 butcher shops, and we had about six or seven bakeries. It was a city within a city,” he says.

But Mihaly is different from most of his neighbors from back then. He stayed. At 91, he still lives in the same house off Buckeye Road that he’s owned for 60 years. As the neighborhood has changed to almost entirely African-American, he’s one of a few dozen Hungarians who remain.

“I stayed because I felt it’s going to come back, not to a Hungarian neighborhood but an integrated neighborhood,” he says.

In the 1940s and 1950s, he says integration seemed possible. His father was friends with a black coworker who lived down the street. The mailman was black, and even spoke some Hungarian.

Mihaly says things started to change after World War II.

“Some of the fellows in the service came home and they were looking for a place to live after they got married,” Mihaly says. "There wasn’t anything for sale in the neighborhood, so they went out in the suburbs.”

That wasn’t an option for black families. At the time, banks wouldn’t lend to African-Americans who wanted to live in the suburbs, and covenants and deed restrictions barred white homeowners from selling to blacks. So as Hungarian churches and businesses moved out of Buckeye, plenty of houses came up for sale and African Americans moved in.

“I would say in the 1970s, early 1970s it started to change more rapidly. It was like overnight,” says Mihaly.

Neighbors no longer felt the same sense of community. And Mihaly said there were some people who were only too happy to fan the flames of fear and distrust.

He owned a building on Buckeye, and there was a realty office inside. Sometimes when he’d drop by to do repair work, he’d overhear phone calls.

“I heard things that weren’t illegal, but it wasn’t ethical,” says Mihaly. “They’d scare some of the older people by saying ‘Well, you better sell because you’re not going to get anything for your building.’”

It was called “blockbusting for profit,” a practice which would eventually become illegal. But for decades, realtors and investors would tell white people the neighborhood was becoming all black, that property values were falling and they should sell while they could. Then the realtors would turn around and sell to black families at above-market prices.

There were times when Mihaly and his late wife thought about selling themselves. But they wanted to live close to their parents, who also stayed. And they never had kids, so more space wasn’t a concern.

Buckeye neighbor Grant Johnson has lived on the same block as Mihaly for the last 25 years. The two men bond over things like car repairs and the Hungarian nut rolls Mihaly brings him from his favorite bakery.

“Yeah, that’s my rappie. We rap and talk all the time,” says Johnson.

Today, Mihaly is the only white person on his block, and he was precinct committeeman for the Republican Party in a neighborhood that’s nearly 100 percent Democratic. But Johnson says Mihaly is a welcome part of the community.

“Everybody respects Ernie. He’s been here, and he’s just one of the people in the neighborhood. That’s the way we look at him,” says Johnson.

Mihaly says it’s people he meets in the suburbs who are the most confused by his decision to stay in Buckeye.

“I tell ’em where I live, then they change their attitude, [saying] ‘Aren’t you afraid?’ And I say no. I can live with black people, Spanish people, as long they respect me and I respect them,” he says.

Mihaly thinks Buckeye has a bright future. University Circle and all its jobs are just down the hill, and he thinks the Opportunity Corridor road project will make the neighborhood easier to reach.

He says when neighborhoods are too homogenous, they get insular. People become suspicious of outsiders. Which is why he doesn’t pine for Buckeye’s Hungarian past: “Like any other ethnic neighborhood in the city of Cleveland, it was clannish. We have our own little island and we want to keep it. I think you should keep your own identity, at the same time be able to communicate with other people,” he says.

For Mihaly, that’s pretty much the meaning of integration: Different people learning to talk to each other. It didn’t happen way back when, but he still hopes it’s possible in the future.

Blockbusting from the black perspective

Probably my biggest takeaway from working on this story was just how many factors played into the way Buckeye changed. I mean, we look back at the history and the data, and the change seems to have happened so fast - 1960, almost entirely white, 1980, mostly black - that it seems like the explanation should also be quick and easy.

But in reality the changes started way before 1960, and there was a lot more going on than just individual people making individual decisions. I don’t have time to get into all of them here, but if you want a really comprehensive history of how banks shut black people out of getting mortgages - first at all, later in the suburbs - check out a book that came out this year, The Color of Law by Richard Rothstein.

But one practice I do want to dive into further here is the whole phenomemon of blockbusting, which I touched on in the story. That’s where realtors used racial scare tactics to get whites to sell their houses, then sold them to blacks for inflated prices. Ernie Mihaly told me about what he heard in his building, but I also wanted to hear about a black family’s experience.

For that, I talked to Barbara Price. She’s a lifelong Clevelander who runs the food pantry program at the Thea Bowman Center in the Mount Pleasant neighborhood, just south of Buckeye.

She has strong recollections of when her parents bought a house in Mount Pleasant in the late 1950s.

"My dad had a lot of problems with the realtors," she says.

The house gave them a lot more space than they’d had before, in their small, overcrowded rental unit in the Central neighborhood close to downtown Cleveland. That’s one of the neighborhoods where blacks had been confined before World War II, despite the fact that the city’s African-American population was booming - from 85,000 to a quarter million between 1940 and 1960.

She was only in eighth grade at the time, so she doesn’t remember all the details, but the move was hard-won.

"My dad had a market price that he wanted to pay for the house and it was almost like the realtor my dad first went to didn’t think he had any idea about purchasing a house," she says.

He thought the realtor was trying to overcharge him.

"My dad argued with the realtor back and forth back and forth before he actually decided to buy the house," she says.

He decided to buy anyway, to make a better life for the family. But the experience was humiliating for him, and he never forgot it.

At the time the family moved in, the neighborhood was becoming integrated, but was still majority white.

"On one side there was an italian family and on the other side I think they were Polish," she says. "Oh my gosh, the realtors almost ran them off the street."

Constant visits, phone calls, letters. But the Italian neighbors in particular stuck it out for a while.

"They were an older couple," she says. "Their children were grown and they had all intentions of staying there until they died. But because the neighborhood was changing so fast, I think the real estate people scared them into moving."

By the time Price graduated from high school, a few years later?

"I think there might have been two white families left," she says.

She says, of course she doesn’t blame only the realtors. There had to be some seed of fear for them to exploit in the first place.

"There’s still that fear of having a black person live next door to you," she says. "There is that fear with some people."

It's still the case today, though she believes tolerance for diversity is increasing.

"I think times are changing. Some people are less afraid than they used to be," she says. "Before, people were just running."

A realtor's memories

I wondered what a realtor would have to say about all this. I mean, someone whose job was selling houses back then - would they admit that this stuff was going on?

"You do something that in your mind is very innocent, and boom, someone else has misinterpreted what you’ve done and here you are," says Gary Zeid.

Zeid is a lawyer with the firm of Sternberg & Zeid, in the Cleveland suburb of Mentor. But in the early 1970s, he was a brand new real estate agent, working for his dad’s company, paying his way through law school.

Sometime right around then, he sold a house in a part of the inner-ring suburb of Cleveland Heights that was still mostly white, but becoming uneasily integrated.

"I sent out a postcard to that general area advising them that I had sold a house in that area and if they needed a real estate agent, they should please call me," he says.

That postcard did not go over well.

"I got I believe it was two letters from I don’t remember who exactly from, I believe they were from street organizations, accusing me of blockbusting," she says. "And I don’t remember the exact wordings but I certainly took it as a threat that I better not do this again."

He says he doesn’t remember if he sold the house in question to a black family or a white. To him, it didn’t matter - Zeid says he was just a realtor doing what realtors do: selling houses.

"I was shocked. I was absolutely shocked. I was looking to sell houses," he says. "And I wasn’t overly concerned as to who I was selling to, whatever color or nationality they were. I was looking to match up a house with the buyer."

The neighborhood never followed up on its threat of legal action against him, but Zeid says he did learn his lesson about one thing.

"I didn’t send out any more of those cards to the neighborhood," he says. "To any neighborhood."

Gary Zeid’s story made me wonder if, at least by the 1970s, blockbusting was more of a spectre than a reality, a term thrown around by white people who were scared of blacks moving into their neighborhoods. After all, the practice was officially outlawed by the Fair Housing Act of 1968. It might have still happened after that, but any realtor using blockbusting tactics in the 1970s would’ve been taking a big career risk.

And then there’s this: in the 1950s and 1960s, some white blocks, somewhere, needed to change. As I said, the city’s African American population almost tripled between 1940 and 1960, mostly as part of the Great Migration from the South, black people looking for jobs and greater equality up North. It just wasn’t possible — let alone ethical — to try to keep African Americans confined to a couple of already crowded neighborhoods close to downtown.

It’s just unfortunate that at the time that critical point was reached, we as a nation, especially our institutions, felt such a need to keep black and white people separate. The territories that ended up being established back then have in many ways kept us frozen in time, thinking of each other as - well, other. Because our paths so seldom have a chance to cross.

Thanks to everyone featured in this piece for being willing to share their stories so honestly, and to the teams at ideastream and NPR’s Code Switch for pushing me to dig into subjects that at first seemed way too complicated to cover.

Thank you for listening, and we’ll see you next time!

14: Secret Stream

At Watershed, we always planned to do an episode about Doan Brook. After all, it’s the reason our show has the title it does, because it ties together all the neighborhoods we cover - Buckeye, Mount Pleasant and Woodland Hills.

Without further ado, here it is!

Hidden in plain sight

A few years ago, I used to live right next to the brook. But I didn’t even know it was there. As I’d drive up busy Fairhill Road to my apartment, I was always aware there was “something,” back there, in the woods at the side of the road. But I didn’t know what.

That’s a lot of people’s relationship with Doan Brook. They don’t know about it, and if they do, they don’t pay much attention. Big deal. A stream.

Then, years after I moved away, I heard there was this really beautiful trail right, through a gorge full of boulders and deer and a waterfall. Basically, I had a secret Narnia right in my backyard, and I never knew it.

So I called up Tori Mills and asked her to show me around. Tori is the director of the Doan Brook Watership Partnership, and all about getting people to care more about this little stream.

"Down in the gorge is extremely quiet and peaceful, an urban oasis," she tells me.

Oh and by the way? There's a waterfall. Who knew?

We’re also joined by Katie Kirtley, a retired post office worker who just got hired to do some public outreach for the Partnership.

Katie lives in the neighborhood, off Buckeye Road, and like me, she’s never been on this hike.

You can tell right away we’re both city people. I’m wearing old hiking boots with laces that won’t stay tied. Katie’s stylishly dressed in a blue blouse, short pants, and scarf - to ward off mosquitoes.

"The most fashionable hiker in the watershed," Tori jokes.

"Yeah," Katie says. "Because otherwise I might get bit by mosquitoes."

On the road

As the three of us walk along Fairhill Road, Tori Mills tells us why it’s important that more people know about Doan Brook in general and the gorge hike in particular.

She says there’s a ton of research that being out in nature can reduce people’s risk of illness. Mental, physical, pretty much everything - from Alzheimer’s to diabetes to ADHD. All from just seeing leaves and squirrels and hearing birds chirping.

Just as an example, one study from Stanford University a couple years ago compared the brains of people who walked in nature with the brains of folks who walked along a busy highway. The researchers looked at the particular brain area associated with depression. In the hikers’ brains, that area lit up way less.

And those benefits may be especially important in the city neighborhoods around the Gorge - Buckeye, Mount Pleasant and Woodland Hills. Poverty rates are 50 percent or more, and a lot of people suffer from high blood pressure, diabetes and mental illness.

"Urban parks are critical to healthier neighborhoods," Tori tells us. "And so making sure this tremendous resource is realized by people around us is critical."

Then she says something that really hits me. In the 70 square miles or so between the Cuyahoga River downtown and Euclid Creek at the city's eastern edge, the Doan Brook corridor provides the only natural green space.

Only. As in, that's it.

When Cleveland was booming back in the early 1900s, nobody thought much about parks. It was all about cramming in as many houses in as little space as possible. Now, Doan Brook is the only place for miles around where us city dwellers can get a workout outside a gym or a busy road.

"In here," Tori says, "this is our chance to really get our heart pumping in a setting that is not a treadmill at the gym with CNN blaring above us, you know?"

There’s a secondary benefit to getting your daily stepcount in the great outdoors.

The more people see the stream, the more they’ll care about it. The more they care about it, the more they’ll want to keep it clean, and that is good not just for the Brook, but for the place where the Brook ends up.

Lake Erie. 18th largest freshwater lake in the world, source of drinking water for 11 million people. Home to one of the richest fish populations in the Great Lakes.

Suddenly, a stream!

And then all the sudden, under an overpass and through a field, there we are: the Brook.

It really is like entering another world. Just a few yards away from the road. Birds chirping. Late summer cicadas.

I ask Katie how she feels.

"Kinda quiet," she says. "Serene."

We walk deeper into the woods, along a trail. Up and then down.

Katie wants to know if there are any snakes.

"That’s a question we get a lot," Tori says, laughing. "That and bears!"

Strategically, though, she doesn't answer.

"I need a stick," Katie mumbles.

"To kill the snake?" I ask.

"No," she says. "Just to flick it somewhere."

And then the grand finale: The waterfall. A real one!

It cascades over some ledges and splashes down into a deep, clear pool.

"If people didn’t believe there was the gorge, they definitely didn't believe there was something as pretty as the waterfall," Tori says.

She says it's at its lowest point all year. Often, you don’t see any rock at all, just whitewater.

As we finish up our hike, we head up a side trail back to Fairhill Road.

"My cardio is on," Katie says with a laugh. "I’m breathing hard."

We emerge from the treeline, back out onto Fairhill, and the modern world. The woods all but vanish behind us.

"Yeah this is something," Katie says. "I didn’t even know this was back here."

I ask how many times she's driven by without noticing the brook or the gorge.

"Oh, thousands," she says. "Thousands. We used to go to the doctor’s office right there at Fairhill."

She pauses.

"Took me like, what, 40 years to find out what’s over here? How about that."

'We don't belong'

A few weeks after our hike, a guy named Dudley Edmondson comes to town. He’s a nature advocate from Duluth, Minnesota, and the author of Black and Brown Faces in America’s Wild Places.

He’s here to give a series of talks about diversifying public parks and nature equity — the idea that everybody — regardless of income level, race, ethnicity — needs access to natural places to feel healthy.

He says as a kid growing up with alcoholic parents, nature for him was a refuge. But being black, that wasn’t something that a lot of his peers understood, or accepted.

"They used to call me Euell Gibbons," he says.

"He was an old white guy on Grape Nuts commercials and he’d always say, 'Did you know many parts of this plant are edible?'

"The kids used to tease me and call me Euell Gibbons because I liked nature, collecting bees and praying mantises. And kids made fun of me because they either thought [those things] were nerdy or stupid things that white people did."

He says the idea that natural places like the Doan Brook gorge aren’t really for black people has deep roots.

"I think for people of color, people not in the dominant culture, I believe there’s probably some level of feeling that things don’t necessarily belong to them," he says. "So if there’s no one living on it, it’s probably owned by either a white person or the city officials but the most important thing is it’s not yours."

Dudley still grapples with that feeling in his own life, even though he’s someone who goes out into nature for a living.

"Even now as an adult I still do not really access land that I’m not 100% sure who the owner is," he says. "I will look for signage before I step onto land."

When he talks about that with white friends, they don't get it.

"They figure if they go on the land and the owner comes out they’ll just explain themselves and everything will go fine," he says. "And as a black man I think, ‘Well first you’ll see the shotgun and then you’ll hear the bullets flying and have to find a way out of that situation.’"

He says that perceived lack of access is the real origin of the old stereotype that black people just aren’t interested in hiking or the woods.

"If people don’t know something exists then maybe that also creates a lack of interest," he says.

When it comes to the Doan Brook gorge, the solution, he says, is just to make it really obvious that it’s a park. As in, open to everyone.

"You really need to put out a welcome mat," he says. "I’m not saying put out a sign, ‘Black people welcome.’ I’m saying, though, do it in a way where the message is communicated, they understand this is a public space and they’re more than welcome."

Having people of color on staff, maintaining and interpreting the park, can also encourage more diversity in vistorship.

Whatever is done, though, it shouldn't be about ‘getting black people to think nature is cool.’

It should be just about making sure everyone has the chance to discover how both stimulating and healing it can be to tramp through fallen leaves. With sun on your skin, and just the sound of birds and water in your ears.

Telling you that your problems - maybe they can be solved. That the world will go on.

That you belong.

13: Two Years and Change

Photos: Seth Beattie, Justin Glanville, Angie Hayes

A little more than two years ago, I moved into the Buckeye neighborhood for a month. The idea was to get an on-the-ground view of the place. Hear its everyday sounds, see its everyday sights. And talk to as many people as I could about their neighborhood and what they wanted for its future.

Recently, I moved back for another month, to see what’s changed, and what hasn’t. And that’s this episode — the sounds, the stories of coming back.

This time, I’m staying with Liz Bartee - known to just about everyone as Ms. Liz. She runs the downstairs apartment of her house as an Airbnb.

I got to know Ms. Liz two years ago when I was staying next door.

She’s a shorter woman in her 70s, with close-cropped blonde hair and glasses. She’s retired from a long career working in manufacturing at General Electric, but she still works part-time, in the evenings, for her daughter’s office-cleaning business.

She’s friendly, but commanding too — this great mix of charm and gravitas. One of her neighbors, Reggie Hines, called her the Queen Bee of E. 117th Street. Ms. Liz is the kind of woman who’s endlessly patient, would do anything for you - but she also doesn’t want your jeans staining her couch, thank you very much.

"Any of your friends come over with jeans on," she tells me, "put the towels on. Sometimes the jeans fade into the couch."

As we wrap up our tour of the apartment, Ms Liz shows me her security system. It’s pretty high-tech — this little computer screen that you slide your finger across to activate.

It gets us talking about neighborhood safety in general. Last time I was here, a lot of the neighbors on 117th Street told me they didn’t feel safe on their own street, especially after dark. A lot of that was because of a group of young men who hung out on the corner. The drug boys, people called them. Teenagers who sold and used drugs, and who’d scatter when cop cars drove by.

"When I was here last," I say, "a lot of people worried about the guys on the corner."

"Right," Ms. Liz says. "Well, they still hang down there but hey, they don’t come this way. They don’t be up and down the street."

The street’s quieter, she says, because a couple of the boys who led the dealing are now gone. One moved away. The other was arrested and incarcerated.

That night, I sit out on the front porch. Ms. Liz is right - it does seem quiet. Mostly what I hear are late-summer cicadas. Some distant ambulance sirens, occasional music.

At the house across the street, a little boy plays with a toy sword that lights up neon red when he swings it.

The block looks pretty much as I remember it. Two-family houses with big front porches, lined up side by side. The back end of a yellow-brick church, enclosed by a hurricane fence. A big community garden on some vacant lots, overflowing with tomatoes, green peppers and cabbage.

I get to thinking about how, even though things look the same, this is a different block than it was two years ago. I know from asking around and keeping in touch with friends that some people have moved away, and others have moved in. The drug boys, for one. But also Reggie Hines, who called Ms. Liz the Queen Bee and himself the Mayor of 117th Street. He died of cancer shortly after our project ended.

I can still picture him hanging out in his driveway, listening to “Clean-Up Woman” by Betty Wright. His daughter Shonnie Settles, who used to wear a yellow flower band in her hair, moved to East Cleveland. Meanwhile, a half-dozen college graduates have started an intentional community called PORCH, in the house on the other side of the community garden.

Looking for change

The next morning, I decide to walk around, seeing for myself what else has changed, or not, in the last two years.

One of the biggest visible changes is, unfortunately, a negative one. The neighborhood grocery store, a branch of the Pittsburgh-based Giant Eagle chain, closed a few months ago. Neighborhood residents and community groups tried really hard to keep it, but in the end, word was Giant Eagle was losing money on the store, and theft was a big problem.

There’s another full-service grocery store a little to the East, a Dave’s Supermarket, as well as an Aldi to the south, so residents still have options.

I think about what a grocery store means, beyond the obvious thing of selling food. The psychological impact of this big empty space is probably even worse than the lack of groceries inside.

I mean, not every neighborhood has a big supermarket, right? And that’s OK. But when a neighborhood that once had one loses it - that’s another matter. That seems to make a statement about the neighborhood’s present, and its future.

I see a couple of young women hanging out on a curb, so I decide to ask them how they feel about the Giant Eagle closing.

"They had the great deals and everything," says Shawnee Derricotte, who lives a couple blocks away. "The fresh fruits, the good meats, it was a nice grocery store."

I ask where she goes now.

"Aldi’s, Sav-a-Lot, Dave’s," she says. "But this was close. This was real close."

Then I talk to a high school kid named Clarence, who’s waiting for a bus after a doctor’s appointment. He reminds me that neighborhood appearances are all relative, a matter of perspective. He grew up in the King Kennedy public housing estate, and now lives at 84th and Central. For him, the closed store’s no big deal.

"I mean, shoot, I think it’s nice up here," he says. "When you come up the way it gets nicer. When you go down it gets worser. I ain’t even gonna fake to you."

As I walk back East on Buckeye, further "up the way," there are bright spots, too.

There’s a new steak and seafood restaurant, Diallo’s. And I see that most of the retail stores I remember from a couple years ago are still here. Nikki’s Music - one of the last independent record stores in Northeast Ohio, proud purveyor of CDs, records and cassette tapes - is still going strong. And Som Di Mma Elegance, an African clothing store.

Some of the empty old storefronts have been covered with brightly painted, billboard-size poems by writer Damien Ware, who lives in the neighborhood. “True love can be found in knowing who you really are,” in blue stenciled letters wrapping around a single-story brick building. “The streets will never love you like a neighborhood should.”

Then, one of my favorite sights in all of Cleveland.

Clyde Johnson, who runs a hot dog and burger stand called CJ’s Famous Angus. I got to know him last time I was in the neighborhood, and have stayed in touch ever since. He’s warm, thoughtful, and you can smell his grilled onions a mile away.

I ask him how things have changed or not in the neighborhood in the last couple years.

"It's kinda hard to say," he says. "I’d say I don’t see as much activity from the drugs thing. Which you know is a good thing."

He thinks the reason for the decreased crime has less to do with police presence than changes in the suspected dealers themselves.

"I think the young guys around here, they’ve seen enough of the guys go down and I would think they’re trying to change their ways a little bit," he says.

The meaning of quiet

Quieter. I think about the dual meaning there. In a way, ‘quieter’ is a good thing. It means less crime, that people are being respectful of each other’s space.

But it also means, maybe, that there’s - well, just more space. And less activity. No grocery store. Not many new businesses. And for a neighborhood that’s been wrestling with declining population and empty storefronts for a while, that kind of quiet’s not such a good thing.

Luckily, right next door to where Clyde Johnson is setting up his stand is the office of someone who can help me make sense of it all.

John Hopkins is executive director of Buckeye Shaker Development Corporation, the neighborhood redevelopment group. We start out talking about - no surprise - the closed supermarket.

"It’s been problematic seeing that big parking lot with no cars in it, you know," he says. "It’s just overwhelming."

People still eat, buy groceries and get their meds, he says.

"But what you do lose is just that comfort, that feeling that I can walk to the corner, ride my bike, take a short drive to the grocery store," he says.

But then he has some good news for me.

"We’re on the verge of securing another grocery store for the neighborhood, so that’s exciting," he says.

It’ll be run by a local operator this time, a guy who has a few other supermarkets in the region. The city just announced a package of loans and grants worth $2 million in the next few months.

Another big game changer, he says, is the mayor’s neighborhood initiative, a pot of $25 million that will go to various underserved neighborhoods, including Buckeye.

That's good news, he says, because "the opportunities [for redevelopment] aren’t as plentiful here as other places."

I ask if the neighborhood needs to change.

"No, no," he says. "It just needs to get better."

But that’s a form of changing, right?

"Well it’s a form of changing, but instead of having a Wendy’s is it possible to get Panera Bread," he says, "or if our demographics don’t line up for that national chain to come, can you get a local person to open like a Panera Bread that offers salads and other healthy options."

A new vocabulary

Sometimes it seems like we need a whole new vocabulary for working in neighborhoods. ‘Change,’ ‘improvement,’ ‘making things better’ - they all imply that there’s something wrong with what’s already here. And the danger there is that it doesn’t just devalue the place - it devalues the people who are living and working on these streets, reinforces this idea that their lives aren’t enough, they’re not enough.

I think John Hopkins was onto something when he said the future is now. How do we settle in to what exists in the present, instead of resisting it and striving for something else? How do we bring the vibrancy and strength of the people who are here now out onto Buckeye Road, so they can be seen by everyone?

On my way back home, I make one last stop - Som Di Mma Elegance. It’s run by Ego Adigwe, from Nigeria.

The store is full of the same racks of primary-colored gowns and hats that I remember from a couple years ago. And while Ego tells me she’s been making things work, that’s mostly because she spends her weekends selling at trunk sales and local outdoor markets. Business in the store itself is almost zero, and she makes no effort to disguise her frustration about that.

"It’s a busy neighborhood as you can see," she says. "The traffic is more than Larchmere, but they’re letting this neighborhood go for some reason."

Larchmere is another commercial street about a mile to the north that seems to be doing a lot better than Buckeye. It’s got an amazing bookstore, a vegan bakery, brand new street trees.

But she's right that Buckeye is busier. According to the regional transportation agency NOACA, Buckeye handles about 10,000 cars a day, compared with about 6,000 on Larchmere.

"But people don’t stop to come in and shop because they’re scared," she says. "And then we have a lot of vacant stores, a lot of abandoned buildings."

She knows about that $25 million pot of money that Mayor Jackson set aside. And she says - what he should do with it is fix up some of the run-down buildings on the street and rent out the storefronts at a reduced rate to entrepreneurs with solid business plans. She says yes, it would be a loss for the city at first, but over time, that would change.

"There’s a lot of people who want a storefront but they can’t afford it," she says. "And then in two or three months they move out."

Rents of about $300 a month, she says, would get people to move into the spaces. She says those initial business owners would stay even when the rent goes up, because now they’re doing well, they want to stay, and they’ll be willing to pay $500, $600 or more for their place.

Absence and presence

That night, back on Ms Liz’s front porch, I think over all I’ve heard. There seems to be a theme to it all. What this place needs, what any place needs, isn’t anything grandiose. It’s just attention, and appreciation. Not change so much as uncovering. That’s pretty much what Ego Adigwe was saying: ‘Hey, we’re here. Give us a chance to do our thing.’

And the hopeful thing is, in John Hopkins’ words, there are actually opportunities now for that to happen. The few million dollars that Buckeye will get from Mayor Jackson’s fund isn’t huge, but it’s a start. And there’s also a crowdfunding site, ioby - that’s i-o-b-y, for in our own backyards - that focuses on projects right in this neighborhood.

I wonder if in another two years, the changes will become more visible. So that it’s not just the absence of things we notice - like the so-called drug boys or the Giant Eagle - but also, their presence.

12: Grandmas Unite!

Photos: Angie Hayes

Peggy Ellen Faulkner was going to get groceries one day. It was not going well.

Her two grandsons were in the backseat, standing up, no seatbelts on. Their mom was up front with grandma, fighting on the phone with her boyfriend. Peggy Ellen couldn’t take it.

"I told her, I said, ‘Look, you need to get yourself together.’ I said, ‘Because they are number one. They are the most important thing in your life and if you don’t get it together I’m gonna take them from you.’"

That definitely quieted things down. There was this stunned silence in the car. Peggy Ellen wasn’t sure where the words came from. The moment passed, life went on.

Then, a few months later, her grandsons’ mom brought the kids over for what was supposed to be just a normal weekend with grandma — reading, watching movies, maybe visiting the zoo.

Peggy Ellen noticed her older grandson had a black eye.

"I asked him what happened to his eye, and he said he fell on the floor," she says. "He had a black eye. You don’t fall on the floor and get a black eye."

It was the beginning of a two-year-long custody battle.

In the end, Peggy Ellen won the fight, and her grandsons moved in. Good news for the boys — a safe home, grandma loved them — but remember that crazy car ride to the grocery store? Now, that was Peggy Ellen’s life. Every. Single. Day.

"I only had one child," she says, "and I was an only child. Two children? I knew nothing about that. And i’m like, 'Lord, why did you send me two? I can understand one but I can’t do two. I just can’t do this!’"

The hardest part was that she felt so alone. She ended up having to retire early from her job as a teacher, so she lost daily contact with her co-workers. And most of her friends her age were kicking back, enjoying their empty nests.

Then Peggy Ellen heard about The Grandmothers Club.

Providing support

That's not actually this group’s real name. That’s just what the 20 or so women who come for the twice-weekly meeting call it. The real name is the Kinship Care Support Group, and it’s open to anyone who’s a primary caregiver to the kid of a relative or close friend.

Grandparents who act as primary caregivers to their grandkids are on the rise. In the last Census, a record 2.7 million grandparents were primary caregivers across the U.S. Some experts say the number may grow as the opioid crisis takes a growing number of parents out of commission.

The club meets a couple times a week at Fairhill Partners, a nonprofit on Cleveland’s East Side that organizes meetings and classes for the elderly. The women at today’s meeting come from all over Cleveland, but mostly from neighborhoods nearby. A lot of their grandkids are right downstairs, at a summer day camp.

There’s Rosa Johnson, a retired teacher who takes care of her two granddaughters. Maxine and Joyce Reynolds, two relatives who attend meetings together. And Alice McCoy, who lives across from the old Saint Luke’s Hospital and tutors kids in the summer camp about math.

They sit around an L-shaped table, telling stories about what’s happening to their grandkids at school, battles with kids’ biological parents, helping out with homework… Sharing advice, tips, or just commiserating.

Get a bunch of grandmas around a table, and you can be sure they won’t run out of things to chat about.

On the day I attend, the grandmas spend their first few minutes kind of half-complaining, half-joking about how kids don’t learn cursive writing anymore.

But then things turn heavier. A couple of the women say they’re concerned about social promotion — how teachers sometimes move kids to the next grade before they’re really ready.

"It’s frustrating to a kid if they start out trying to do something and they can’t," says one grandmother. "And then everything you do, the next thing builds on so the kid is frustrated from the jump."

Not alone

Peggy Ellen Faulkner chimes in with her own story, about her younger grandson, who brought home F’s on his report card.

"I called the school and said, 'I know you’re not passing him.’ [They said] ‘Ms. Faulkner, what are you talking about?’ [I said] ‘He got an F in reading and an F in math. He’s not being passed, i’m telling you now.’ They’re like, 'Ms. Faulkner —’ ‘No, i don’t want to hear it. He’s not passing.’"

You might think, from the confident way she talks, that Peggy Ellen fit right into this group from the beginning, no problems. But actually, when she came to her first Grandmothers Club meeting about four years ago, not long after she was asking God why he sent her two grandsons, she was nervous.

"I didn’t want to talk because I didn’t know anybody," she says. "And they made everybody introduce themselves and when they got to me it just seemed like all the sudden I just opened up."

She found herself telling her whole story. The black eye, the custody battle, how she’d never tried raising two kids at the same time before.

And all around the table, she saw other women her age. Nodding their heads. Listening.

They were looking back at her like she was one of them.

"With open arms, you know? And like it’s all right," she says. "Because I did kinda come to tears for a minute but they let me know it was all right. I was safe."

She pauses.

"You think you’re alone but you’re not."

Comfort and crying

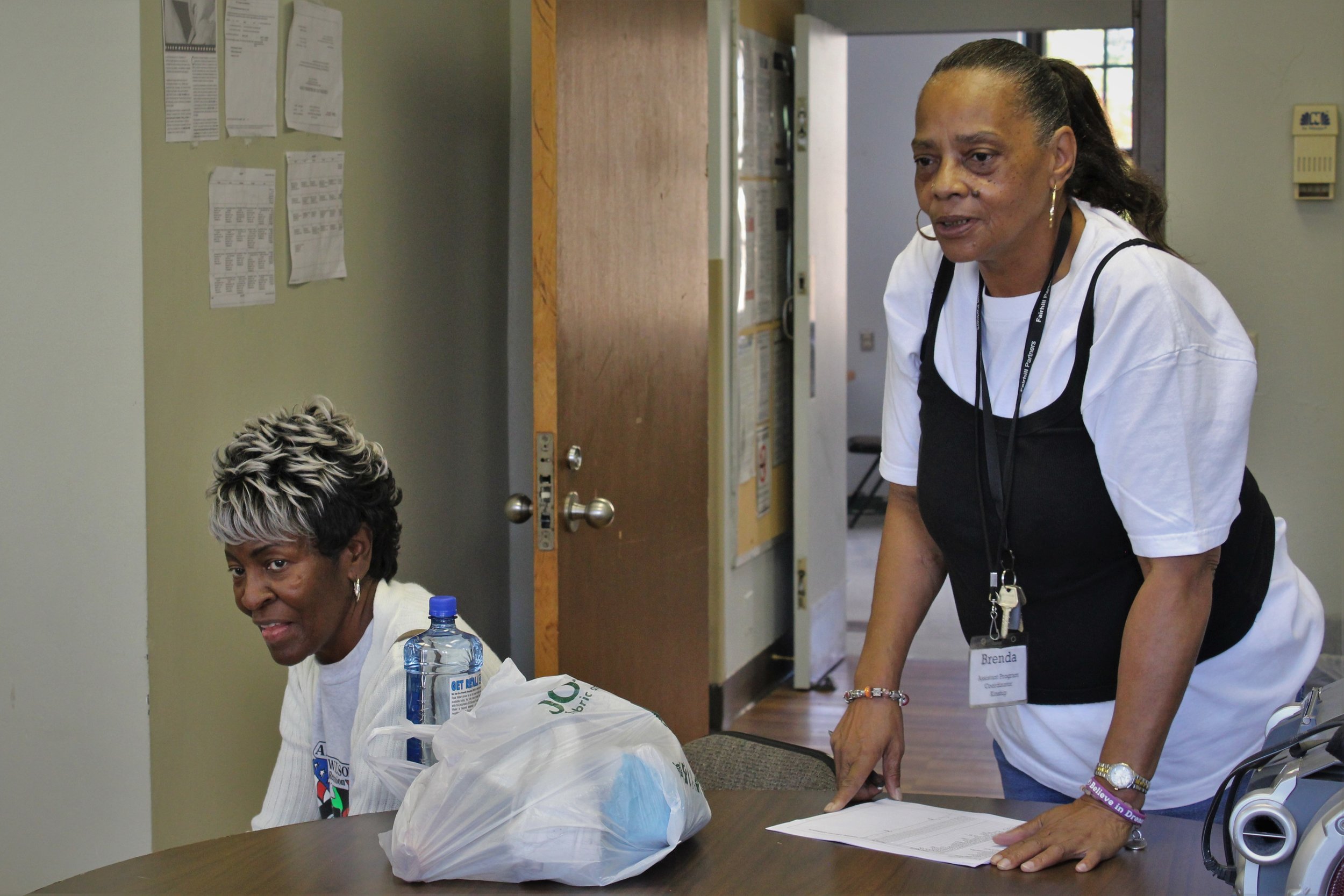

According to Brenda Cheatham, who organizes the group for Fairhill Partners and is also a member, that may be the chief value of the Grandmothers Club - feeling, for at least an hour or two a day, that you’re not alone.

"We have a camaraderie," she says. "If I’m having a problem, nine times out of 10 the other grandma has had that problem. And she can help me, direct me, comfort me, we cry together."

Cheetham also brings in professionals to give talks. Not just about how to raise grandkids, but how grandmas can keep themselves healthy, too. That’s important for aging people who have to chase toddlers at a stage of life when most people are slowing down and taking it easy.

"If they come in and say, 'Well, Brenda, I want to know about diabetes, can you get a nurse to come in? Can you get a lawyer that deals with seniors? Then I try to find a lawyer."

A recent study showed that grandparents’ health initially declines when they take in grandkids, probably due to the jolt of activity and stress that kids bring. But if grandparents find the resilience — and support — to stick it out, the study said their health actually improves over what it was pre-kids.

Peggy Ellen Faulkner has a theory about why.

"If you sit down and do nothing, I found out, you waste away," she says. "Not just physically but mentally. So with them around, physically I had to move around, but then I always needed to be thinking, reading things, teaching them."

Resting and doing nothing may have sounded good, she says, but the reality may have been far different.

"I’m glad they’re here," she says. "They’re gorgeous, they’re beautiful, they need me — and I need them."

And for all the times when they, or their teachers, are driving her crazy — or when she’s just feeling lonely — she says she needs the Grandmothers Club, too.

11: Bringing Yoga to 'Her Village'

Note: This episode was a collaboration between Watershed and ideastream, Cleveland's public media outlet. Also check out a short video version of the story.

There’s no zen-like music playing in the background, no incense burning, no stretchy yoga clothes, and it’s not at a studio or even a traditional gym. But it is a yoga class, and it’s happening at Zelma George Rec Center, in the Mount Pleasant neighborhood of Cleveland.

With the sound of the bell, about 30 or 40 kids lie down on their mats. A lot of them have just finished eating the free lunch the center provides. The neighborhoods around the rec center have some of the highest poverty rates in the region.

By the latest counts, more than half of all residents, and nearly three quarters of all children, live below the poverty line.

“What does yoga do for us? It works on our flexibility balance and strength,” said yoga teacher and Buckeye-Shaker resident Kimberly Archibald Russell. She says one reason she became a yoga teacher was to help the people around her cope with the problems that come along with poverty, which include stress and a lack of healthy food.

“Just like everyone else, I see people that are heavy, I see people that are smoking, and I just see that they need a better way of life,” she said.

In Mount Pleasant, about half of adults have high blood pressure — twice the national average. One in five report mental health problems such as depression. And these conditions aren’t unique to Mount Pleasant. In many neighborhoods where poverty rates are high, chronic physical and mental illness have become persistent problems. Some residents, like Russell, are confronting disease not just through doctors and drugs — but techniques to manage long-term stress.

“I just want folks to know there’s things they can do to help,” said Russell.

Russell teaches in two city rec centers, public schools, a community center, all within a mile or two of her house. Her company, My Village Yoga, is all about bringing her neighbors the benefits of yoga. (She also works with ZenWorks Yoga, which brings yoga to public schools.)

“Calmness, serenity, control, discipline—it’s just introducing it. That’s what I’m trying to do,” she said.

The fact that Russell lives in the neighborhood, and looks like the residents she’s teaching, helps her overcome the stereotype of who yoga is supposed to be for. “People that practice yoga aren’t necessarily white skinny females. It’s all of us,” she said.

One time, she was walking into an elementary school on the East Side, she recounts, “and a little girl who had been in my first class, said, ‘There’s my favorite yoga teacher!’ and I said ‘Oh, I’m your favorite yoga teacher even though this is only our second time meeting?’ and she said ‘Yes. You’re brown like me.’”

Lamont Thomas, a 20-year-old supervisor at Zelma George, says that after only a couple classes he’s already hooked on how calm he feels after taking a class. “I never did yoga before,” he said. “Subconsciously I didn’t know I was breathing slower than I was before I started. Then I started noticing I was taking deeper breaths. And that’s cool,” he said.

Another organization in the neighborhood, Fairhill Partners, also offers a range of classes to help people stay healthy.

“Zumba, Pilates, yoga, tai chi, all of those are a good fit for somebody,” said Fairhill’s director, Stephanie FallCreek.

FallCreek says hospitals and doctors are important, but they tend to focus on treating sickness rather than on maintaining health. In neighborhoods like Mount Pleasant, she said, “we have a wealth of healthcare services and a poverty of access to a certain kind of preventive and proactive self-management approaches to doing the best we can with the health that we have, and with the resources that we have.”

Which is exactly why yoga instructor Kimberly Archibald Russell says she hopes her students take what they learn back to their families.

“Oftentimes at the end of the class, I’ll say, ‘Now comes our true practice of yoga, after we roll up the mat and go home,’” Russell said.

10: The Red Tires

Donald Wilson stands on his front porch, surveying Parkview Avenue, the street where he lives in Cleveland's Woodland Hills neighborhood.

"I cannot believe that people do not have that much respect for those who do live here," he says. "I mean, they wouldn’t do it next door to their homes, I know they wouldn’t. But they do it in my neighbors’ yards."

Parkview has been his home for decades. Some people, though, see it as one big trash can.

He points across the street.

"You’ll see there had been some illegal dumping," he says. "That home is vacant, unoccupied."

I follow the direction of his pointing. There's a big pile of trash at the rear of the house's driveway.

"So people back their cars up in there and they dump in the backyard?" I ask.

"Yes, and for the most part they do it where it’s vacant houses on either side, but here they chose to do it where there’s an (occupied) home on either side," he says.

Donald tells me he's done all the things you’d expect. He calls the city, his councilman, his local neighborhood organization. And sometimes they help out. But still, the trash just keeps coming.

So he and a group of neighbors decided to fight back themselves. By taking some of that trash that gets dumped, and turning it into a warning sign.

'They choose dumping'

He leads me to the most recent of a half-dozen or so dumps within walking distance of his house.

It's sitting in a vacant lot next to an unoccupied house, and contains a couch, some tree debris limbs, bags full of clothing, paperwork, toys...

It all started, he says, about 8 or 9 years ago. He thinks there are a couple reasons. First, the foreclosure crisis meant that Woodland Hills started emptying out faster than ever, leading to hundreds of vacant houses and unused yards. Second, to help balance their budgets, Cleveland and some inner-ring suburbs started charging people for trash pickup. And raised their fees for, big, bulky stuff like mattresses and furniture. What they call “excessive set outs.”

"They either have too much to dump or only one week a month to put out large bulk items," Donald says. "And they’ll get fined when they do it not that week. So they choose illegal dumping."

The trash doesn’t just look bad, he says. It’s also really dangerous. Kids can get hurt stepping on broken glass. There are big, sealed bags of mysterious objects that may or may not be hazardous.

After seeing this happen for months, Donald and some of his neighbors started organizing cleanups every other Saturday morning. They put on big latex gloves, grab a few of those long-reach trash-pickers with claws on the end, and get to work.

An idea dawns

It was on one of those Saturdays a few months ago that Donald got an idea.

"We were finding tires dumped on treelawns in the street," he says. "So in our cleanup efforts we were taking these tires and putting them on the curb."

It struck Donald that instead of just throwing the tires out, maybe they could serve a purpose.

"I said, 'What if we try to use those tires as barriers? What if we cut them and put enough of them together that it can be a barrier that says, stop, don’t do this."

Donald cut some tires in half, into semi-circles. He bolted a half dozen or so, curved side up, to a four by four, so they’d be too heavy to move.

Donald walks me to a house around the corner, to show me his first barrier.

It sits right at the end of the driveway, a few feet back from the sidewalk.

And the way it’s positioned, the tires look almost like a dragon tail, emerging from the asphalt. It’s not just the shape of them, but the fact that they’re painted a bright, fire-engine red.

"Why red?" I ask.

Donald doesn't hesitate to answer.

"Because red says stop," he says. "It really says stop."

Stop. Don’t trash my neighborhood.

"This is where I live at, this is where I work at, this is where I pray at," he says. "It’s my neighborhood and I want to see it thriving."

Neighbors approve

A couple of Donald’s neighbors step outside to say hello. His neighbor Eileen says she’s a big fan of the red tires.

She remembers when she first saw them.

"I thought, 'Well golly, what’s that all about?' And then when i found out I said, 'That is just perfect, seriously. Just perfect.' Because they do do a lot of dumping."

No patent pending

Donald’s a pretty modest guy, so he’s not trying to patent his tire barriers or tell other neighborhoods where dumping is happening that they should use them too.

Right now, he’s just watching his first couple installations. Making sure they work. So far they are, but he doesn’t underestimate how persistent dumpers can be.

"A contractor may just roll right over these with their big dump trucks, I don’t know," he says. "I hope not. I hope it’s gonna work, because we need to do something to prevent it."

I ask if he has a name for the barrier project. Like, the Red Tire Initiative, or Project Red Tire. Something snappy to help them raise money or awareness.

He says no, not really.

"We haven’t titled it anything," he says. "Just effort. That’s it. Just effort to prevent the dumping."

Effort to prevent a neighborhood from being seen as disposable itself.

9: Walk With a Cop

Photos: Angie Hayes

The relationship between police and low-income communities of color has been strained for a long time.

Cleveland is no exception.

When a Cleveland cop shot and killed 12-year-old Tamir Rice in 2014, it led to accusations that police see and treat black people differently than whites — and far too often, with violence. The federal government is now requiring the city’s police department to track how and when it uses force, and to make more of an effort to build community trust.

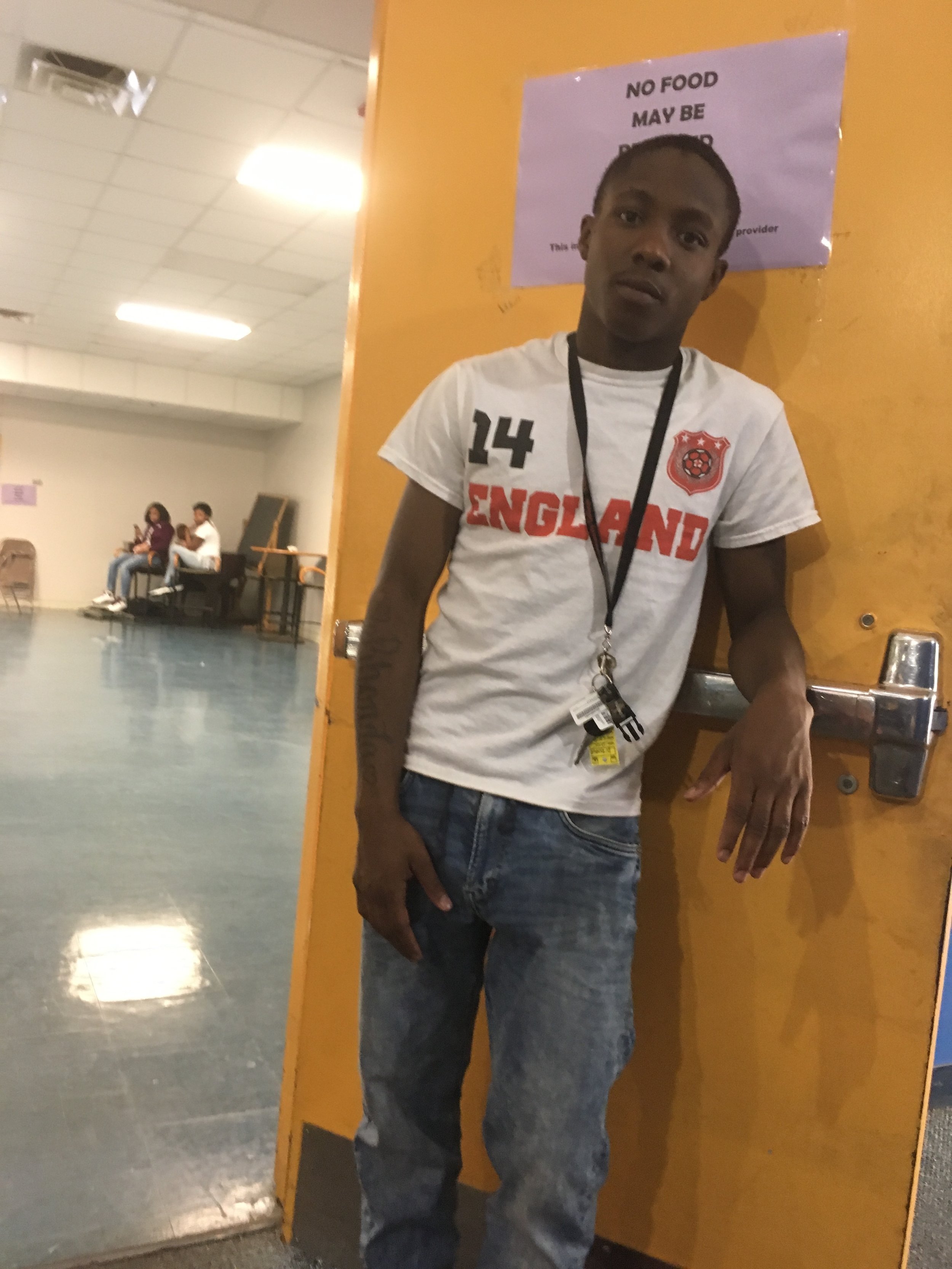

Cops are under scrutiny. In Cleveland, they’re still walking their beats, patrolling the city’s neighborhoods — but now they’ve got new company.

On this episode of Watershed, an urban hike. Led not by naturalists or boy scouts or teachers, but by uniformed cops.