Photos: Seth Beattie, Justin Glanville, Angie Hayes

A little more than two years ago, I moved into the Buckeye neighborhood for a month. The idea was to get an on-the-ground view of the place. Hear its everyday sounds, see its everyday sights. And talk to as many people as I could about their neighborhood and what they wanted for its future.

Recently, I moved back for another month, to see what’s changed, and what hasn’t. And that’s this episode — the sounds, the stories of coming back.

This time, I’m staying with Liz Bartee - known to just about everyone as Ms. Liz. She runs the downstairs apartment of her house as an Airbnb.

I got to know Ms. Liz two years ago when I was staying next door.

She’s a shorter woman in her 70s, with close-cropped blonde hair and glasses. She’s retired from a long career working in manufacturing at General Electric, but she still works part-time, in the evenings, for her daughter’s office-cleaning business.

She’s friendly, but commanding too — this great mix of charm and gravitas. One of her neighbors, Reggie Hines, called her the Queen Bee of E. 117th Street. Ms. Liz is the kind of woman who’s endlessly patient, would do anything for you - but she also doesn’t want your jeans staining her couch, thank you very much.

"Any of your friends come over with jeans on," she tells me, "put the towels on. Sometimes the jeans fade into the couch."

As we wrap up our tour of the apartment, Ms Liz shows me her security system. It’s pretty high-tech — this little computer screen that you slide your finger across to activate.

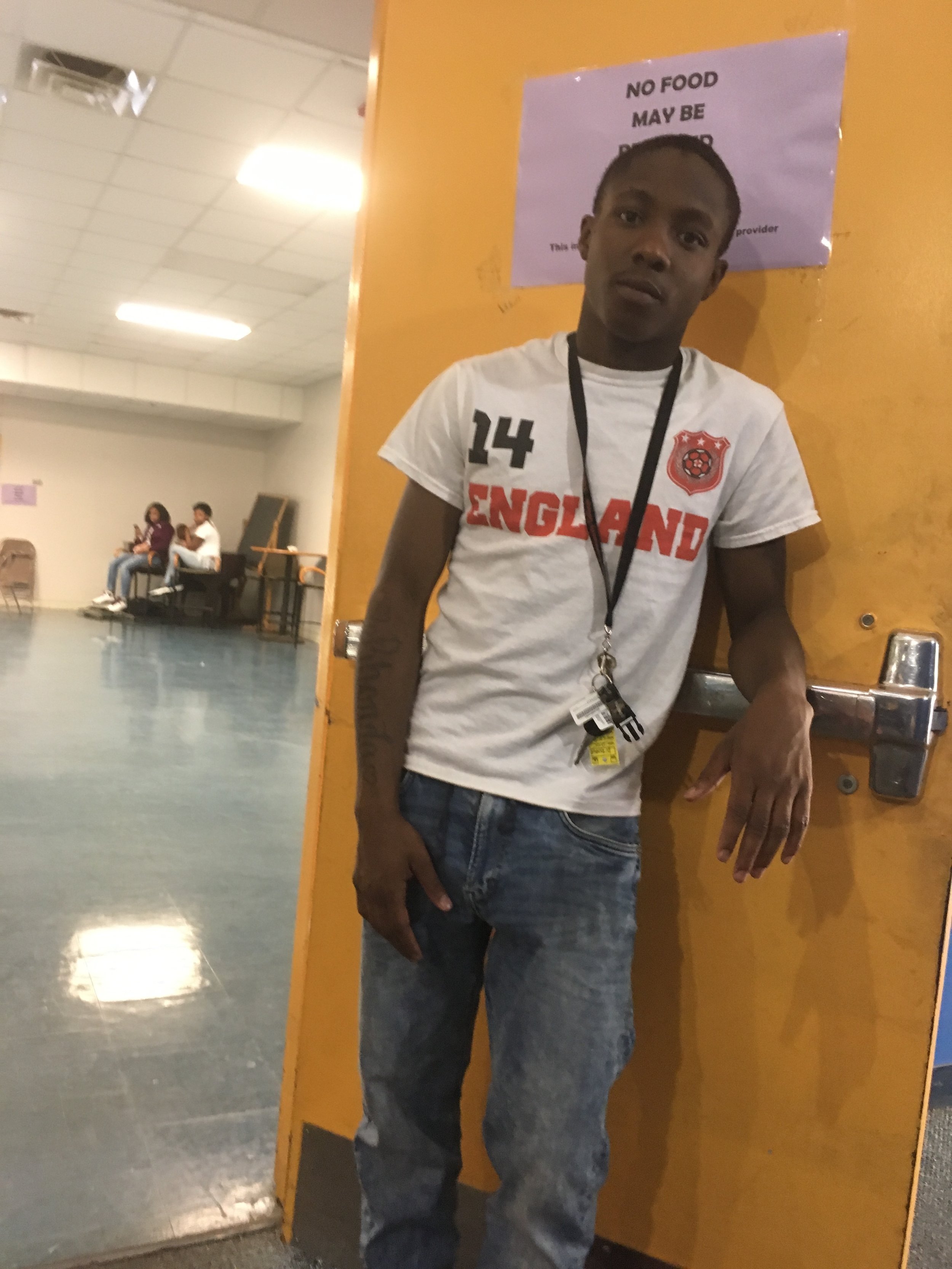

It gets us talking about neighborhood safety in general. Last time I was here, a lot of the neighbors on 117th Street told me they didn’t feel safe on their own street, especially after dark. A lot of that was because of a group of young men who hung out on the corner. The drug boys, people called them. Teenagers who sold and used drugs, and who’d scatter when cop cars drove by.

"When I was here last," I say, "a lot of people worried about the guys on the corner."

"Right," Ms. Liz says. "Well, they still hang down there but hey, they don’t come this way. They don’t be up and down the street."

The street’s quieter, she says, because a couple of the boys who led the dealing are now gone. One moved away. The other was arrested and incarcerated.

That night, I sit out on the front porch. Ms. Liz is right - it does seem quiet. Mostly what I hear are late-summer cicadas. Some distant ambulance sirens, occasional music.

At the house across the street, a little boy plays with a toy sword that lights up neon red when he swings it.

The block looks pretty much as I remember it. Two-family houses with big front porches, lined up side by side. The back end of a yellow-brick church, enclosed by a hurricane fence. A big community garden on some vacant lots, overflowing with tomatoes, green peppers and cabbage.

I get to thinking about how, even though things look the same, this is a different block than it was two years ago. I know from asking around and keeping in touch with friends that some people have moved away, and others have moved in. The drug boys, for one. But also Reggie Hines, who called Ms. Liz the Queen Bee and himself the Mayor of 117th Street. He died of cancer shortly after our project ended.

I can still picture him hanging out in his driveway, listening to “Clean-Up Woman” by Betty Wright. His daughter Shonnie Settles, who used to wear a yellow flower band in her hair, moved to East Cleveland. Meanwhile, a half-dozen college graduates have started an intentional community called PORCH, in the house on the other side of the community garden.

Looking for change

The next morning, I decide to walk around, seeing for myself what else has changed, or not, in the last two years.

One of the biggest visible changes is, unfortunately, a negative one. The neighborhood grocery store, a branch of the Pittsburgh-based Giant Eagle chain, closed a few months ago. Neighborhood residents and community groups tried really hard to keep it, but in the end, word was Giant Eagle was losing money on the store, and theft was a big problem.

There’s another full-service grocery store a little to the East, a Dave’s Supermarket, as well as an Aldi to the south, so residents still have options.

I think about what a grocery store means, beyond the obvious thing of selling food. The psychological impact of this big empty space is probably even worse than the lack of groceries inside.

I mean, not every neighborhood has a big supermarket, right? And that’s OK. But when a neighborhood that once had one loses it - that’s another matter. That seems to make a statement about the neighborhood’s present, and its future.

I see a couple of young women hanging out on a curb, so I decide to ask them how they feel about the Giant Eagle closing.

"They had the great deals and everything," says Shawnee Derricotte, who lives a couple blocks away. "The fresh fruits, the good meats, it was a nice grocery store."

I ask where she goes now.

"Aldi’s, Sav-a-Lot, Dave’s," she says. "But this was close. This was real close."

Then I talk to a high school kid named Clarence, who’s waiting for a bus after a doctor’s appointment. He reminds me that neighborhood appearances are all relative, a matter of perspective. He grew up in the King Kennedy public housing estate, and now lives at 84th and Central. For him, the closed store’s no big deal.

"I mean, shoot, I think it’s nice up here," he says. "When you come up the way it gets nicer. When you go down it gets worser. I ain’t even gonna fake to you."

As I walk back East on Buckeye, further "up the way," there are bright spots, too.

There’s a new steak and seafood restaurant, Diallo’s. And I see that most of the retail stores I remember from a couple years ago are still here. Nikki’s Music - one of the last independent record stores in Northeast Ohio, proud purveyor of CDs, records and cassette tapes - is still going strong. And Som Di Mma Elegance, an African clothing store.

Some of the empty old storefronts have been covered with brightly painted, billboard-size poems by writer Damien Ware, who lives in the neighborhood. “True love can be found in knowing who you really are,” in blue stenciled letters wrapping around a single-story brick building. “The streets will never love you like a neighborhood should.”

Then, one of my favorite sights in all of Cleveland.

Clyde Johnson, who runs a hot dog and burger stand called CJ’s Famous Angus. I got to know him last time I was in the neighborhood, and have stayed in touch ever since. He’s warm, thoughtful, and you can smell his grilled onions a mile away.

I ask him how things have changed or not in the neighborhood in the last couple years.

"It's kinda hard to say," he says. "I’d say I don’t see as much activity from the drugs thing. Which you know is a good thing."

He thinks the reason for the decreased crime has less to do with police presence than changes in the suspected dealers themselves.

"I think the young guys around here, they’ve seen enough of the guys go down and I would think they’re trying to change their ways a little bit," he says.

The meaning of quiet

Quieter. I think about the dual meaning there. In a way, ‘quieter’ is a good thing. It means less crime, that people are being respectful of each other’s space.

But it also means, maybe, that there’s - well, just more space. And less activity. No grocery store. Not many new businesses. And for a neighborhood that’s been wrestling with declining population and empty storefronts for a while, that kind of quiet’s not such a good thing.

Luckily, right next door to where Clyde Johnson is setting up his stand is the office of someone who can help me make sense of it all.

John Hopkins is executive director of Buckeye Shaker Development Corporation, the neighborhood redevelopment group. We start out talking about - no surprise - the closed supermarket.

"It’s been problematic seeing that big parking lot with no cars in it, you know," he says. "It’s just overwhelming."

People still eat, buy groceries and get their meds, he says.

"But what you do lose is just that comfort, that feeling that I can walk to the corner, ride my bike, take a short drive to the grocery store," he says.

But then he has some good news for me.

"We’re on the verge of securing another grocery store for the neighborhood, so that’s exciting," he says.

It’ll be run by a local operator this time, a guy who has a few other supermarkets in the region. The city just announced a package of loans and grants worth $2 million in the next few months.

Another big game changer, he says, is the mayor’s neighborhood initiative, a pot of $25 million that will go to various underserved neighborhoods, including Buckeye.

That's good news, he says, because "the opportunities [for redevelopment] aren’t as plentiful here as other places."

I ask if the neighborhood needs to change.

"No, no," he says. "It just needs to get better."

But that’s a form of changing, right?

"Well it’s a form of changing, but instead of having a Wendy’s is it possible to get Panera Bread," he says, "or if our demographics don’t line up for that national chain to come, can you get a local person to open like a Panera Bread that offers salads and other healthy options."

A new vocabulary

Sometimes it seems like we need a whole new vocabulary for working in neighborhoods. ‘Change,’ ‘improvement,’ ‘making things better’ - they all imply that there’s something wrong with what’s already here. And the danger there is that it doesn’t just devalue the place - it devalues the people who are living and working on these streets, reinforces this idea that their lives aren’t enough, they’re not enough.

I think John Hopkins was onto something when he said the future is now. How do we settle in to what exists in the present, instead of resisting it and striving for something else? How do we bring the vibrancy and strength of the people who are here now out onto Buckeye Road, so they can be seen by everyone?

On my way back home, I make one last stop - Som Di Mma Elegance. It’s run by Ego Adigwe, from Nigeria.

The store is full of the same racks of primary-colored gowns and hats that I remember from a couple years ago. And while Ego tells me she’s been making things work, that’s mostly because she spends her weekends selling at trunk sales and local outdoor markets. Business in the store itself is almost zero, and she makes no effort to disguise her frustration about that.

"It’s a busy neighborhood as you can see," she says. "The traffic is more than Larchmere, but they’re letting this neighborhood go for some reason."

Larchmere is another commercial street about a mile to the north that seems to be doing a lot better than Buckeye. It’s got an amazing bookstore, a vegan bakery, brand new street trees.

But she's right that Buckeye is busier. According to the regional transportation agency NOACA, Buckeye handles about 10,000 cars a day, compared with about 6,000 on Larchmere.

"But people don’t stop to come in and shop because they’re scared," she says. "And then we have a lot of vacant stores, a lot of abandoned buildings."

She knows about that $25 million pot of money that Mayor Jackson set aside. And she says - what he should do with it is fix up some of the run-down buildings on the street and rent out the storefronts at a reduced rate to entrepreneurs with solid business plans. She says yes, it would be a loss for the city at first, but over time, that would change.

"There’s a lot of people who want a storefront but they can’t afford it," she says. "And then in two or three months they move out."

Rents of about $300 a month, she says, would get people to move into the spaces. She says those initial business owners would stay even when the rent goes up, because now they’re doing well, they want to stay, and they’ll be willing to pay $500, $600 or more for their place.

Absence and presence

That night, back on Ms Liz’s front porch, I think over all I’ve heard. There seems to be a theme to it all. What this place needs, what any place needs, isn’t anything grandiose. It’s just attention, and appreciation. Not change so much as uncovering. That’s pretty much what Ego Adigwe was saying: ‘Hey, we’re here. Give us a chance to do our thing.’

And the hopeful thing is, in John Hopkins’ words, there are actually opportunities now for that to happen. The few million dollars that Buckeye will get from Mayor Jackson’s fund isn’t huge, but it’s a start. And there’s also a crowdfunding site, ioby - that’s i-o-b-y, for in our own backyards - that focuses on projects right in this neighborhood.

I wonder if in another two years, the changes will become more visible. So that it’s not just the absence of things we notice - like the so-called drug boys or the Giant Eagle - but also, their presence.